Five years ago, on my first Halloween in the Big City (I didn’t know I was a small town girl until I moved to Los Angeles), my nightmare materialized. You never think it can happen to you, but it always does. I calmed myself, as I always do, by telling myself: “Remember, Interesting and Strange things happening to you are a good thing because you will be able to use them in a screenplay later.” I sat there trying to figure out what to do next, when a cop knocked on my window. I suddenly found myself on the side of a Los Angeles freeway during rush hour (in LA “rush hour” means going 15 mph, backwards) in the dark. “Are you okay ma’am?” he asked just like they do in the movies. “Yes, my car just…died.” I noticed the traffic slowing down…to…look…at me, on the side of the road. I was in a position to make a long time fantasy come true. To yell at them: “Idiots! You’re making traffic worse! Move along, move along, there is nothing to look at here!” But I didn’t.

I could not believe the tow truck guy didn’t offer me a ride home after he asked me if I was going to be okay and I said, “I don’t know because I have only been in LA for two months and I don’t know where I am and I don’t have many friends in LA and look at my face don’t I look freaked out?” How uncivilized of him. I left my car at the closest Pep Boys and started to walk. More like wander aimlessly with a freaked out expression. Where in the hell was I? I called my roommate to see if she would pick me up. “Where are you?” she asked. I stopped to survey my surroundings. I took a big whiff and recognized the stench which permeated the air: pozole, menudo and tortillas. There were no white people around. All the signs were in Spanish. “I think I’m in Tijuana,” I told her. “This place makes North Hollywood look like Beverly Hills.” I looked over to the horizon and I saw bright, tall, shiny buildings. “Never mind. I’ll figure out how to get home. I see downtown LA from here and I can take the underground from there.”

“Remember, Interesting and Strange things happen to you when you are forced to ride public transportation,” I kept on saying to myself as I walked to the bus stop. After 30 minutes, the bus finally arrived. I got on and asked the driver if he was going anywhere near the Metro station. He gave me an angry nod and I got on.

I tripped on Jesus and his disciples having their last supper when I got on. The owner of the very large plastic shopping bag gave me a very angry look. “Perdon, Señora” I said as I fought against the forward momentum of the speeding bus. I managed to hang on to a metal pole and swung around with stripper-worthy bravado, my ass serendipitously falling into a seat at the front. I tried to regain my dignity by pretending to check my voice-mail messages and turning up my snooty façade to the max, avoiding eye-contact with the other passengers, which I knew were gawking at me. I again asked the bus driver if he was going downtown. He mumbled a syllable that I chose to interpret optimistically as a yes because we seemed to be moving toward the bright lights. The woman kept staring at me. Then she would look down at her bag. Then up at me. Then at her bag. What did she want me to say? “Sorry I kicked Judas in the gut. Helloooo? You know he deserved it!” I looked at Jesus. He seemed to be looking back at me. I’m thinking I am hungry and that neon colored last supper is looking pretty good to me right now. I’m thinking I want that bag. Just as I was about to ask the woman where she bought it, the bus stopped and she got off, but not without shooting me one last death glare. Vaya con Dios to you too. I again asked the bus driver if he was going to the subway station. I heard a faint mumble. I asked again while trying to read his lips. I decided his response was a yes since things were going so well for me so far.

Sitting in the subway thinking about my dead car and looking at all the miserable, tired faces around me, I wondered when I had lost the ability to feel sorry for myself. I examined their expressions, trying to decipher the details. I felt curious about their lives, but was thankful I wasn’t them. Then, a crowd of black kids got on, followed by a wave of kids in Halloween costumes. Nigger this, nigger that. Nigger this, nigger that. No you ain’t Dorothy, you look like a maid. You lyin’ girl. No, I ain’t, I’m a slutty Dorothy. Aight.

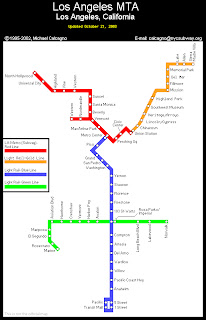

I felt ashamed when I caught myself cringing at their colorful verbal expression of individuality and my unconscious elitism brought to the surface the snobbery I worked so hard to suppress. Why are coherent, well constructed sentences necessarily better than the fascinating lexicon of the oppressed masses? I wondered what neighborhood in Los Angeles produced such charming youngsters. I looked up at the Metro map. Yellow to Pasadena. Unlikely. Green to Norwalk. Haven’t even heard of that place. Red to Downtown, Hollywood and North Hollywood. That was where they were going. Orange to the Valley. That was where I was going. Dotted yellow to East L.A. Under construction. Blue to Central L.A. and Long Beach. Most likely. I wondered what chance these kids had at a decent life. I wondered if they were going to grow up to be bitter bus drivers who don’t like to answer questions. I wondered when Bob Dylan songs started depressing me instead of inspiring me.

A vast white area of the Metro map popped out like a hot spot in a cheap video monitor. The West Side. Not even a faint dotted line indicating a future Metro line. The multi-colored metro diagram illustrated exclusion with the clarity of a shroom trip. The subway system in LA is designed to keep out. I felt smug an oh-so-clever at my realization. Could this be the sign I was waiting for? My call to arms? An apparition not in the form of a saint, but a diagram? It wasn’t at all like my fantasy of Che materializing out of a burning bush and telling me I was the next one, but it was good enough. I pictured myself leader of the revolution. The leader of a guerilla made up of Beverly Hills Mexican maids, brown, short men who wash other people’s BMWs and agent-less screenwriters who’d rather live in a spacious Valley apartment than in a closet in Venice or Santa Monica.

First, we would demand a Pink Line to Boys Town. Everyone should be able to travel to Melrose on an expeditious manner. After all, the pretty people shopping need to be gawked at while they purchase yet another pair of $200 jeans or drink organic tea at Urth Cafe. When the Revolution gathered momentum and my guerilla was fully-trained, we would move on to Santa Monica. La Resistance would require the tactics of an insurgent group and we had to be prepared for a tough fight. Santa Monica meter maids are worthy adversaries and they will not give up their commissions without some ass whooping. “Take your parking tickets and shove them down your fascist ass!” would be our call to arms. Then, Beverly Hills and Rodeo Drive. We would build a wall around it to keep those silly, stupid rich people in. They would be able to keep their shit, but not allowed to go anywhere else.

I pictured Los Angeles as a Southern California Paris, but without the cool cafes, the pain chocolat and the culture. Subway lines connecting everyone. And all thanks to me. I would be known as The Ter. Berkeley students would walk around campus wearing t-shirts with my face on them. I saw murals of me painted in all the new Metro stations. Then I realized my motives were purely selfish. Most of the art-house cinemas were in the West Side and I wasn’t sure when I’d have money to buy a reliable car.

By any means necessary, right? Well, not really. The Revolution didn’t go past the planning stages. I recovered financially and bought a new car as soon as I could. Also, I never ride public transportation. It’s not that I don’t want to. I can’t because I take my dog to doggy daycare on my way to work every day. Someone else will have to lead the revolution. It’s a Wall Street government, the teacher unions have ruined public education and the Polar Bears have drowned. I’m busy being disillusioned and pessimistic.