Wednesday, June 30, 2010

Can PMS be a good thing?

I’m very critical of my writing, especially when it comes to my screenplays. Ninety-nine percent of the time I think I’ve written shit and the other 1%, well, something that just might work and be worthwhile.

It really doesn’t help that I’ve won awards and that people have told me they love my scripts. Instead of feeling validated, I start to question the judges’ capacity for judging good work. Seriously. It’s probably because I don’t measure my work up to today’s standards. My standards are much higher. I look up to Billy Wilder, Preston Sturges, Paddy Chayefsky, Stanley Kubrick, Ernst Lubitsch. I can’t think of a script that was written after 1990 that I wish I had written. I wish I had written All About Eve, It Happened One Night and Annie Hall; not Avatar, The Hangover or Sex and the City. My screenwriter friend James keeps on telling me to lower my standards. He sends me Black List scripts to show me what Hollywood considers good these days. But I just can’t seem to lower my standards. I’m not even close.

Generally, reading drafts of my work is a rollercoaster of emotions, mostly negative. But I’m currently reading a draft of my latest and I’m enjoying it and thinking it works. It’s a strange feeling I am unable to trust. Where is the doubt, the second-guessing and the self-hate I’m so familiar with? It finally dawned on me. It’s the PMS. This week I’ve been bombarded by PMS-related physical maladies and last night I choked up during Wheel of Fortune.

Anyone that knows me will tell you that I’m a thinker, not a feeler. I took an acting class once and the teacher told me I’d never be able to act because I was a head in a cart. I also failed Yoga for Dummies. So, is this abnormal emotional state making me think I’m a better writer than I really am or is it suppressing the part of the brain that processes logical thought? Shouldn’t it be the opposite? Shouldn’t this cry-baby temporary condition make me hate my writing even more? I have no way of knowing. I’m not changing any time soon. I am how I am. Hard on myself.

I don’t have any answers. All I know is that from now on I will make it a point to read my work while PMSing because the feeling is good. And today I will take advantage of the situation and send out the script before I change my mind, which should be any minute now, right after I have a good cry and a cookie.

Tuesday, June 29, 2010

You want me here for sex, don't you?

One of my friends has gone wild filling out Flixter Top 5 lists on Facebook and one in particular caught my eye: Top 5 George Romero. The omission of a particular movie made me gasp with indignation, especially since my friend (yeah, you Freddy!) is supposed to be a huge Romero fan. I pointed out this injustice (or what I concluded had to be a lapse in judgment due to the fact that he gets too much oxygen up there in Eugene, Oregon) and he replied that he had not seen it. Whuuuut???

Those who call themselves horror fans (Freddy) already know Martin well (not Freddy). After his initial 1968 success with Night of the Living Dead, Romero had three box-office failures, resulting in his switching to making documentaries for four years. In 1977 Romero returned to feature film making with Martin, a study of a troubled youth who may or may not also happen to be a vampire. Over the past 30 years Romero's vampire work and his personal favorite, has attracted a strong following of admirers. It’s undeniable that this 1970s reworking of vampire mythology is a multi-layered achievement which demands serious consideration. Martin was for some time Romero’s most talked about but least seen film, the perfect conditions for the birth of a cult, and one whose steady growth has been matched by an increased critical appreciation of the horror film as a vehicle for social commentary.

Vampires have been really “in” for quite some time. The development of the genre has seen the figure of the vampire shift steadily in locale and class, moving closer to home and descending in rank as the years have passed. It has given us a lot of classics (Nosferatu, Vampyr), but it wasn’t until Martin that everything changed. (Let the Right One In is not as original people might think.) Very much a film of its changing times, Martin was the first vampire movie to completely shake off the genre's folklore origins and the shadow of novel that effectively shaped the first 50 years of vampire cinema. It recognized the shifting nature of both the horror audience and the fears of the society in which they live, a post-Charles Manson era in which you could be killed for no even remotely logical reason by the guy who lives just down the road. This is recognized even in the film's title. Like Dracula, the most famous vampire tale of them all, the name of the vampire is the name of the film, but whereas “Dracula” invokes a sense of the exotic, the mysterious, the foreign, Martin is deliberately ordinary, an everyday name that has no specific connotations other than its day-to-day familiarity.

Martin brought the vampire onto our doorstep and stripped him of nobility – he is an ordinary kid and he lives in a spare room in his cousin's house. He has no bride, no girlfriend, and unlike the sexually potent vampire of films past, is actually afraid of women and sex. Martin is the boy next door, the reclusive, uncommunicative kid, the loner that Homeland Security would peg as having terrorist potential. He's the shy boy who one day shocks the neighborhood by doing something horrible and out of character that, just for a few moments, makes him special. Most of all, he is the product of his family and environment – all his life he has been told he is bad and now he believes it and acts accordingly.

Romero sets his story in a decaying Pittsburgh suburb populated by aging, superstitious immigrants. Romero's pseudo-vampire is Martin (John Amplas), an awkward teenager with few social skills and a sadistic habit of feeding off the blood of innocent victims he methodically drugs and rapes. But despite his thirst for blood, Martin doesn't have vampire's teeth; he's immune to crucifixes, garlic and priests. So what exactly is he? Fortunately, Romero never answers this question and opts instead to define Martin as a product of his environment, a town populated with ugly, superstitious, immoral, criminal and suicidal depressed individuals. As evidenced in a number of scenes, if Martin doesn't kill you, life will.

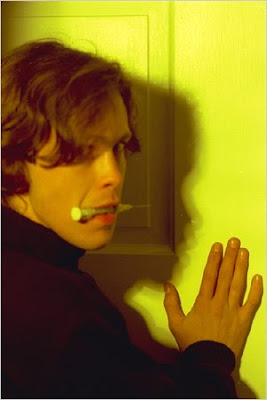

In perhaps the most iconic image in modern vampire cinema, Martin is briefly framed at his victim's door with a syringe held ready in his mouth (the image will recur later). The needle replaces the fang – both are used to sedate and ultimately destroy the vampire's prey, but while the traditional elongated canine teeth link the vampire to the wolf into which he is fabled to transform, the syringe has, for most, very unpleasant real world associations. It's clinical, surgical nature directly reflects Martin's approach to his assaults, which are executed like military stealth operations. Brilliantly constructed and edited (the use of rapidly cut huge close-ups is particularly impressive), this is a nonetheless deliberately confrontational and uncomfortable opening. How could any audience sympathize with such a central character? Enter Tada Cuda. But I will stop right here, for fear I might spoil it for those who have not seen the movie (Freddy!).

Even though the quality of Martin is hampered by its budgetary restraints, these flaws help Martin transcend the typical constraints of the vampire genre. As a result, Martin is afforded the ability to be disturbing in ways that emulate the horrors of raw, real-world footage. Martin concludes with an abrupt, brutal and final act, an act that puts to death the significance of whether Martin was or wasn't a vampire. In the end, all that matters is how cold and unforgiving the world is and how it leaves us with few choices. The ultimate choice and perhaps the worst one of all: Kill or be killed.

Ironic as it may be, it’s also typical of great true independent cinema that one of the most intelligent and revisionist of modern vampire movies may not be a vampire movie at all. It's a question that has hovered over the film ever since its release and is central to its narrative – is Martin Madahas an 84-year-old vampire or a mixed-up kid with psychotic tendencies? This may be the primary question asked throughout Martin, but it isn't the most important one. The question worth asking is: nature or nurture? Romero's script is one of his best, a (literally) biting commentary on a post-Watergate, post-Vietnam, blue-collar America: disillusioned, depressed and depraved. Either way, Martin is a genuinely great vampire movie, one that recognizes and fully understands generic conventions and yet turns most of them completely on their head.

Martin takes the codes and conventions of the vampire genre and reworks them to remarkable ends, with one eye on the past but the other fixed firmly on the society in which the film was made. In that respect it has to be seen as the first truly modern vampire film, a strikingly intelligent, inventive and socially relevant take on a genre that even in the 70s was still hanging onto the coat-tails of the Transylvanian Count whose story gave it birth. Martin contemporized the vampire tale, not by transporting Dracula to swinging London in 1972, but by exploring modern fears through modern eyes and confronting the audience, perhaps for the first time, with what it really means to be a vampire. That it remains so fresh a work today is, ironically, in part due to its lack of mainstream success. When commercial cinema eventually re-embraced the vampire film in the 1980s, it had learned little from Romero's extraordinary work, the younger protagonists of The Lost Boys – dressed to look cool and pining for MTV – having more to do with audience demographic than a desire to explore the genuine fears of society or the traumas of youth. In this respect Martin is even today a unique work, a low budget gem of extraordinary depth and complexity that showcases Romero on phenomenal form both as storyteller and filmmaker, and built around an utterly convincing central performance by the young John Amplas and a support cast of largely natural nonprofessionals. There is simply no contest here – Martin is THE modern vampire film. End of story.

Friday, June 25, 2010

There’s more to Tijuana than just donkey shows and cheap meds.

Last night I attended the first of two parts of a Tijuana films showcase at Echo Park Film Center. The program was curated by celebrated, award-winning filmmaker Giancarlo Ruiz, who just got back from Cannes where his film St. Jacques was part of The Short Film Corner.

Last night’s line-up was:

Under the Sycamore Tree-- Joseph Perez

Invasion de los Chinos--5y10 Producciones

Abraham Avila --

Antropofagos-- Abraham Sanchez

33 ½ -- Aaron Soto

Issbocet-- Ricardo Silva --

Los Z-- Giancarlo Ruiz

I will try to review the films next week, but from what I’ve seen from Tijuana filmmakers in the past and from what I saw last night, the films definitely share a vision of the border. The themes and styles are definitely influenced by the region and the city’s quasi dystopian status as outsider; neither belonging to the U.S. nor to the rest of Mexico.

Only Ricardo Silva and Ruiz were in attendance, but the Q &A session was lively and fascinating. The filmmakers’ enjoy outsider status within the Mexican movie-making machine. Silva pointed out that even though they were only 3 hours away from Mexico City by plane, and 3 hours from Los Angeles by car, they could not be farther away from both. Yet, filmmaking is thriving in Tijuana. More and more films are being shot and universities have taken note and have started to offer classes in film and video.

IMCINE pretty much controls the funds for filmmaking in Mexico. It is a very capital-centric fraternity. Their films are always technically first rate; slick and accomplished, and quite different from the Tijuana product. Silva expressed that it was the technical and stylistic differences that made their films beautiful. They don’t have worry about shooting on film because they can’t and they don’t worry about breaking the rules because they don’t have to. It’s this kind of freedom that makes their films exciting and fresh.

Ruiz illustrated this elitism and the mafia-like mentality of IMCINE. In Cannes, he ran into representatives of IMCINE who showed him their list of filmmakers and films at Cannes. He asked them why he was not on the list, since he was, in fact, a Mexican filmmaker at Cannes. Their answer was pretty much, if you’re not an IMCINE filmmaker, you don’t exist. So, if you’re not with IMCINE, you are on your own with no hope of ever receiving funds from the federal government. This is, of course, the modus operandi of almost every industry in Mexico.

Not long ago, the Mexican government passed a law to help filmmakers find private sector funding for their projects. On paper, it looks great. Corporations fund your movie and in turn they get a tax write off. According to Ruiz and Silva, this is problematic, since it has turned out to be a tax racket. They give you an amount of money (allegedly the budget), you make your film for a fraction of the budget, and return the rest to the corporation. It sounds like reverse money laundering to me. Can you imagine if we had such a law in the U.S.? For now, U.S. filmmakers will have to settle for Kickstarter and the like.

Rather than let frustration hold them back, these filmmakers have embraced their limitations and chosen to go ahead despite the difficulties of trying to create in a corrupt and closed system. They will make their films, there is no question about that. However, distribution, as we all know, is a different matter altogether. As it turns out, the handful of festivals in Mexico cater to IMCINE as well. For now they have to settle with self-organized screenings and the internet.

I celebrate Tijuana filmmakers’ tenacity, but when I asked them if they ever thought about their audience, it seemed they had heard the word for the first time. You can’t worry about distribution without first knowing who your audience is. I know the product will continue to evolve and improve and I hope that soon these talented filmmakers will take note of The Audience and discover how far they can go if they make the effort to nurture it.

If you happen to be in Los Angeles, please come to EPFC tonight and check out these films. It might be your only chance.

Tijuana Filmmaker Showcase

June 24-25, 2010 @ 8:00 p.m.

$5.00 at the door

1200 N Alvarado St. (@ Sunset Blvd.) Los Angeles, CA. 90026

(213) 484 - 8846

info@echoparkfilmcenter.org

Monday, June 21, 2010

I'm breathing all right.

Despite having absolutely no chance of being selected as a participant, this year I decided to apply for the Sundance Screenwriter’s Lab. On April 29th, I sent a blank self addressed-stamped postcard along with my application packet. I wrote: “Don’t hold your breath!!!” with a black Sharpie. I figured I’d stick the returned postcard on my fridge and forget about it until I received the “Thank You for Applying” rejection email at the end of the summer.

Today, a friend sent me an email saying he was thankful he didn’t apply because he came across some information on a board. Greg Beal has been the coordinator of the Nicholl Fellowships since 1989 and had this to say about the Lab:

"Entering Sundance as a writer only is problematic. Yes, scripts will be requested on the basis of the pages and synopsis from hundreds of entrants, but the lab participants will mostly be drawn from folks who fit at least some of the following:

1) invited entrants who completely bypass the first cut process;

2) writers and writer-directors known to the Sundance administrators and/or mentors;

3) writer-directors who have had shorts and/or a feature in previous Sundance festivals;

4) writers with some combination of attachments (i.e., director, producers, actors);

5) writers and writer-directors with a film at the project stage (various elements and some or much financing in place);

6) writers and writer-directors recommended to the Sundance administrators by established film folks (often festival and lab regulars).

I was told years ago by one of the Sundance administrators that they were seeking projects that needed one extra push in order to go into production. Consider this example: Ed Burns was a lab participant (with She's the One) after Brothers McMullen was an indie hit.

What writer competition entrants can hope for is: a miracle; or notice this year that will cause them to be invited to submit in a later year."

It doesn’t take the love child of a rocket scientist and a brain surgeon to figure out that’s Sundance’s MO. All you have to do is look up the Lab participants’ resumes and credits to conclude what Greg Beal says above. I do not fit any of the above categories, and I do not hope for a miracle. There’s no such thing as a miracle in screenwriting.

I hope to advance beyond the first round and receive a request for the full script, and, if not, at least get on Sundance’s radar for when I need that “extra push.” You have to get those scripts out there. It’s the only way they are going to get read by people in the industry.

By the way, I got the postcard back with a note that said “Smart girl.”

Today, a friend sent me an email saying he was thankful he didn’t apply because he came across some information on a board. Greg Beal has been the coordinator of the Nicholl Fellowships since 1989 and had this to say about the Lab:

"Entering Sundance as a writer only is problematic. Yes, scripts will be requested on the basis of the pages and synopsis from hundreds of entrants, but the lab participants will mostly be drawn from folks who fit at least some of the following:

1) invited entrants who completely bypass the first cut process;

2) writers and writer-directors known to the Sundance administrators and/or mentors;

3) writer-directors who have had shorts and/or a feature in previous Sundance festivals;

4) writers with some combination of attachments (i.e., director, producers, actors);

5) writers and writer-directors with a film at the project stage (various elements and some or much financing in place);

6) writers and writer-directors recommended to the Sundance administrators by established film folks (often festival and lab regulars).

I was told years ago by one of the Sundance administrators that they were seeking projects that needed one extra push in order to go into production. Consider this example: Ed Burns was a lab participant (with She's the One) after Brothers McMullen was an indie hit.

What writer competition entrants can hope for is: a miracle; or notice this year that will cause them to be invited to submit in a later year."

It doesn’t take the love child of a rocket scientist and a brain surgeon to figure out that’s Sundance’s MO. All you have to do is look up the Lab participants’ resumes and credits to conclude what Greg Beal says above. I do not fit any of the above categories, and I do not hope for a miracle. There’s no such thing as a miracle in screenwriting.

I hope to advance beyond the first round and receive a request for the full script, and, if not, at least get on Sundance’s radar for when I need that “extra push.” You have to get those scripts out there. It’s the only way they are going to get read by people in the industry.

By the way, I got the postcard back with a note that said “Smart girl.”

Tuesday, June 15, 2010

Pass This Bitches!--The Reader, Friend or Foe?

This past Saturday I was fortunate enough to attend a very informative workshop with Julie Gray while attending the Broad Humor Film Festival. The topic was: The World of Readers. I know what you're thinking. Who gives a shit? I thought it for a second too. But quickly I realized how this knowledge would help me get an edge over the rest.

Julie started by describing the conditions under which our scripts are read. There's a hierarchy in the world of readers. When they start out, they have to read for crappy companies and work their way up. On average, they get paid $60 a script. That means they have to read 3-4 scripts a day to make a living. Although some companies are distributing scripts via e-mail, a lot are still very protective and will only use hard copies. This means the readers have to drive all over town to pick up scripts and they don’t get reimbursed for mileage. If they get a call and they turn down a screenplay, they risk not being called again, so the successful readers never turn down work. Also, they get no benefits and no health or dental insurance.

You have to assume they’re not reading your script at 9:00 a.m. with a delicious cup of coffee, but at 11:00 p.m. with a toothache, (remember, no dental insurance) and still two more scripts to go. The first thing they do is turn to the last page to see how long it is. If it’s more than 110 pages, you’ve started really badly. Next, they read the title, which sets the mood. Then, they dump the brads in a bucket and start speed reading. They just read and do not think. If problems that start to come up, they start to think and that slows down the read.

They have to read the whole script so that others don’t have to. Readers can only afford devote 2.5 hours to covering a script. It takes them about an hour to read and the rest for writing the coverage. Coverage is basically 2-3 pages of synopsis and 1.5 pages of comments and notes. If the synopsis is dull, guess what else was dull? Yup. Our script. And dull makes the readers very, very cranky.

Their world is a mine field. There are politics involved and they do have to read a lot of crappy fluff because of who's attached. However, honest, objective readers succeed and are willing to risk their jobs for a great script. Julie reiterated that readers love nothing more than reading a great script. If they come across a RECOMMEND, they call a 24/7 phone number. That’s the executive’s number. The response is always: “Great. Now thanks to you I have to read this weekend.” But they're willing to duke it out and defend the script.

Basically, it’s up to us to make either friends or enemies from readers. It’s on you to make it easier on yourself, and Julie was kind enough to tell us how.

Top Ten (Actually Eleven) Reader Hates

11. Script is too long. This means it’s over 120 pages and it signals that the writer does not have control over her story. Writers should try to hit the 100-110 sweet spot. Comedy and horror scripts should be around 100 pages. Minimum page count is 90 pages. "But so and so's script won an Oscar and it was 160 pages--" You're not so and so and that's an exception. Again, do you want to make it easier on yourself or not?

10. Sending weird shit with the script. Yes, as bizarre as it sounds, people do that. It makes you look like an amateur. Resist all temptation to send the hilarious monkey that's in your script.

9. Nothing happens. Readers see this all the time. They call them BOSH scripts: Bunch of Shit Happens. These scripts are usually episodic, derivative and very boring.

As you can see, she’s getting crankier.

8. Schizophrenic scripts. Screenplays that are all over the place that make the reader ask “What am I reading?” They can’t discern the genre and the tone changes from scene to scene. This means the writer doesn’t know what they're doing and what story they are telling.

7. Sluglines that suck and clutter the page. A lot of times writers read shooting scripts and use that format. You do not need to repeat the slugline over and over. If you’re creative and know cinematic language, you can use sluglines to your advantage. Why say INT. HOUSE when you can say INT. CRUMBLING SHACK? That also eliminates description in the action line. Take every opportunity to seduce with colorful words.

They love mini sluglines. Here’s an example:

INT. MANSION--DAY

IN THE KITCHEN

Jane drops her panties. Joe gets on his knees.

Lubricate the read.

Also, you do not need to keep repeating it’s day. It’s DAY until it’s not DAY anymore. It’s NIGHT until it’s not NIGHT anymore.

And crankier…

6. Lame two-dimensional characters who do not seem to have a backstory or no other life besides the plot. Characters are what make you care about the story. Bad characters have no flaws or motivation and do not change. Don't fall in love with your character at the beginning of the story. If you do, she'll be Miss Perfect, just like you. Fall in love with your character as she is going to be at the end of the story. The protagonist should start like this : ( and end up like this : ).

Remember: A story is an emotion delivery system that should provide catharsis. Great characters are the Gold Standard.

5. On the nose dialogue. There is not such thing as good characters and bad dialogue or vice versa. They are always, without exception, both good or both bad.

4. Too much black. They just skip dense action lines, so your effort to create novelistic prose-like script is wasted and resented. Again, it’s 11:30 p.m., reader has a toothache, no dental insurance and still has two more scripts to read. Aim for less black. Think "white space is the new prose."

Put the reader in the character’s shoes and manipulate her into the movie.

Don't micromanage actors in action lines and give too much detail. The writer is not the director or actor.

No weird editorials: “This should be shot like that scene in Showgirls…”

Do not recommend actors.

Pop references are all right if they are integral to the story.

Break up action to lead

EYES

towards the

BOTTOM of the page.

Lubricate...

Use words as

TRAMPOLINES!

They want to read elegant,

pithy,

cinematic ACTION!

And still crankier…

3. Action Line Interruptus.

Dialogue interrupted by business that means nothing to the story. It breaks up rhythm.

2. Adept imitations. Derivative, unoriginal scripts.

Writers should test their ideas. Write a logline. Then come up with 3-4 movies that are in any way like it. When were they released? What was the Box Office? What was the zeitgeist when the movie was released? Know what kind of movie you are writing. Is it a Friday night blockbuster or a quite indie for a rainy Sunday afternoon?

Are you feeling empathy yet?

1. Typos.

Readers will overlook a reasonable amount of typos. It’s considered petty and in bad form to point out typos in coverage. But if it’s excessive, they're going to mention it because it means it's a writer who has no respect for the English language. A huge flag is the misuse of homonyms, especially if it's all over the script. It means it's not a typo and that the writer does not know the difference.

So now you know how to make it easier on yourself. Make it easy on the reader so that her toothache doesn't get worse and she won’t resent you. And remember, lubricate, lubricate, lubricate. You want words that will slide down a white page towards the magical

FADE OUT.

BTW: The reader tracking board is a myth. No one has any interest or time to bash a script online. They might, if ever, talk about a script if it was ridiculously funny, but that’s about it.

Monday, June 14, 2010

Broad Humor

This weekend I attended the Broad Humor Film Festival as screenplay finalist. It was a fun-filled weekend, and, among many things, I:

1. Spent a total of 6 hours driving to and from Venice.

2. Saw some pretty funny shorts.

3. Met a lot of accomplished filmmakers and screenwriters.

4. Participated in a great screenwriting workshop with Julie Gray.

5. Got some invaluable insights into AFI’s Directing Workshop for Women.

6. Learned that we still need men to move heavy furniture.

8. At the screenwriters’ lab, I heard actors read my Jewish character as Latino and my Latino characters as New Jersey Italians.

9. Indirectly made a woman bawl on her husband’s shoulder. Then cry some more. Then bawl some more until she only had dirty looks left.

10. Won. (See no. 9.)

I will be elaborating on no. 4 for sure, and maybe on other stuff, later in the week.

1. Spent a total of 6 hours driving to and from Venice.

2. Saw some pretty funny shorts.

3. Met a lot of accomplished filmmakers and screenwriters.

4. Participated in a great screenwriting workshop with Julie Gray.

5. Got some invaluable insights into AFI’s Directing Workshop for Women.

6. Learned that we still need men to move heavy furniture.

8. At the screenwriters’ lab, I heard actors read my Jewish character as Latino and my Latino characters as New Jersey Italians.

9. Indirectly made a woman bawl on her husband’s shoulder. Then cry some more. Then bawl some more until she only had dirty looks left.

10. Won. (See no. 9.)

I will be elaborating on no. 4 for sure, and maybe on other stuff, later in the week.

Thursday, June 10, 2010

The Ughline

A commercial director friend who is trying to break into features recently asked me to read a script he’s thinking of directing. Because the scripts he has sent me before have been atrocious, I told him I’d read the logline and go from there.

After I read the “logline” which was actually a logparagraph, I replied:

“This got you to read this script?

I’m sorry, but I can’t devote precious time to reading a script from a writer who doesn’t know the simple structure of a logline. I am sympathetic, don’t get me wrong. I used to write convoluted crap like this too. Five years ago. But, if a writer can’t articulate her story into a simple, exciting sentence, then she has to go back and look at the story structure. Usually the problem lies therein.”

He replied:

“You should read the script before making comments like that. It’s excellent writing.”

I replied:

“I’m judging the ‘logline’. There is nothing in it that makes me want to read the excellent script you speak of. I’m going by the writing and nothing else.

Sorry if it seems harsh, but that’s the reality of trying to make it as a professional screenwriter. You get once chance and one chance only to make an impression and you better make sure you know your stuff. (I give my own dear friends a two-page chance.) That logline made an impression with me and it screamed beginner. Pass.

Eventually those of us who want to improve and actually sell something, take notice and realize what our job is. If my logline doesn't make someone want to read the first pages of the script (and eventually the whole script), then it’s my failure as a writer. I either wrote a shitty logline, or I wrote a story no one wants to read or make into a movie. It really is quite simple.”

I think most writers that are just starting out think they are too good for loglines or even synopses. It’s a travesty to try to condense our genius into one sentence or one page! How dare they? How dare they ask us to do such a thing?

I don’t think it’s a travesty anymore. And it’s not just a marketing necessity, it’s also a valuable tool. Struggling with the logline makes you nail down your story before you begin to write it. And, more importantly, it lets you know whether or not you have a hook or an interesting premise before you go any further and end up writing a character-driven indie with great dialogue and compelling characters no one wants to produce because it's not high concept.

Yet, it’s surprising that most people, even some professionals have difficulty writing a good, effective logline. Just take a look at some of the loglines from last year’s Sundance Lab participants. (According to the webpage, the descriptions were provided by Sundance.)

“40 Days of Silence” by Saodat Ismailova (writer/director), Uzbekistan: Four generations of women under one roof in Uzbekistan look to each other for comfort as they try to overcome their destinies.

“Bluebird” by Lance Edmands (writer/director), USA: In the frozen woods of an isolated Maine logging town, one woman’s tragic mistake leads to unexpected consequences, shattering the delicate balance of her community.

"Drunktown’s Finest" by Sydney Freeland (writer/director), USA: Three Native Americans - a rebellious father-to-be, a devout Christian, and a promiscuous transsexual - find their self-images challenged, and ultimately strengthened, as they come of age on an Indian reservation.

“Zero Motivation” by Talya Lavie (writer/director), Israel: A sometimes comic, often dramatic look at the power struggles of three female clerks over one year in an administrative office at a remote army base in the Israeli desert.

These screenplays got into one of the most prestigious screenwriting programs in the world, so I’m sure they are good scripts. But are these vague loglines effective? Where’s the hook? Where’s the premise? Let’s be honest. If these loglines were not attached to the Sundance brand, they would not make us want to read the script.

In case you're wondering: The logline of your screenplay is a simple sentence or two that acts as a short synopsis of your story and provides the emotional hook that will make any agent or producer wish to read your script. You include the logline of your screenplay within your initial query letter whenever you are soliciting interest in your script from an agent or producer.

A well written logline should be carefully thought out. You have two sentences at most to convince people that your script is worth the time and effort to read, which will hopefully lead to a sale. A logline is also a useful time-saving device. If you are talking about your screenplay to anyone (from friend to Hollywood star) and they ask you what it’s about then you can simply quote your logline (but try not to sound like you memorized it). There should be something about that logline which really stands out and makes whoever hears it want to read the full story.

Your logline also allows you to “big up” your story so it sounds as high concept as possible. Producers love high concept scripts as they are easy to market. That means even if your story isn’t particularly high concept you can use you logline to embellish on it’s most intriguing points. Take note Sundance.

Again, there are two main reasons why you need a logline:

1. A logline keeps you focused as you write.

2. You need a logline to sell your screenplay.

Here are three questions to ask yourself as you write your logline:

1. Who is the main character and what does he or she want?

2. Who (villain) or what is standing in the way of the main character?

3. What makes this story unique?

The Fugitive: After he's wrongly convicted of murdering his wife, a high-powered surgeon escapes custody and hunts down the real killer, a one-armed man.

Memento: A man, suffering from short-term memory loss, uses notes and tattoos to hunt for the man he thinks killed his wife.

Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind: A couple undergo a procedure to erase each other from their memories when their relationship turns sour, but it is only through the process of loss that they discover what they had to begin with.

Contests will also ask for loglines. Even your granny is going to ask for a logline. There's no way around it.

I may have been a little harsh with my friend, but that's exactly how I am going to be judged as a writer. Do you want to be perceived as a professional or as an amateur wannabe?

After I read the “logline” which was actually a logparagraph, I replied:

“This got you to read this script?

I’m sorry, but I can’t devote precious time to reading a script from a writer who doesn’t know the simple structure of a logline. I am sympathetic, don’t get me wrong. I used to write convoluted crap like this too. Five years ago. But, if a writer can’t articulate her story into a simple, exciting sentence, then she has to go back and look at the story structure. Usually the problem lies therein.”

He replied:

“You should read the script before making comments like that. It’s excellent writing.”

I replied:

“I’m judging the ‘logline’. There is nothing in it that makes me want to read the excellent script you speak of. I’m going by the writing and nothing else.

Sorry if it seems harsh, but that’s the reality of trying to make it as a professional screenwriter. You get once chance and one chance only to make an impression and you better make sure you know your stuff. (I give my own dear friends a two-page chance.) That logline made an impression with me and it screamed beginner. Pass.

Eventually those of us who want to improve and actually sell something, take notice and realize what our job is. If my logline doesn't make someone want to read the first pages of the script (and eventually the whole script), then it’s my failure as a writer. I either wrote a shitty logline, or I wrote a story no one wants to read or make into a movie. It really is quite simple.”

I think most writers that are just starting out think they are too good for loglines or even synopses. It’s a travesty to try to condense our genius into one sentence or one page! How dare they? How dare they ask us to do such a thing?

I don’t think it’s a travesty anymore. And it’s not just a marketing necessity, it’s also a valuable tool. Struggling with the logline makes you nail down your story before you begin to write it. And, more importantly, it lets you know whether or not you have a hook or an interesting premise before you go any further and end up writing a character-driven indie with great dialogue and compelling characters no one wants to produce because it's not high concept.

Yet, it’s surprising that most people, even some professionals have difficulty writing a good, effective logline. Just take a look at some of the loglines from last year’s Sundance Lab participants. (According to the webpage, the descriptions were provided by Sundance.)

“40 Days of Silence” by Saodat Ismailova (writer/director), Uzbekistan: Four generations of women under one roof in Uzbekistan look to each other for comfort as they try to overcome their destinies.

“Bluebird” by Lance Edmands (writer/director), USA: In the frozen woods of an isolated Maine logging town, one woman’s tragic mistake leads to unexpected consequences, shattering the delicate balance of her community.

"Drunktown’s Finest" by Sydney Freeland (writer/director), USA: Three Native Americans - a rebellious father-to-be, a devout Christian, and a promiscuous transsexual - find their self-images challenged, and ultimately strengthened, as they come of age on an Indian reservation.

“Zero Motivation” by Talya Lavie (writer/director), Israel: A sometimes comic, often dramatic look at the power struggles of three female clerks over one year in an administrative office at a remote army base in the Israeli desert.

These screenplays got into one of the most prestigious screenwriting programs in the world, so I’m sure they are good scripts. But are these vague loglines effective? Where’s the hook? Where’s the premise? Let’s be honest. If these loglines were not attached to the Sundance brand, they would not make us want to read the script.

In case you're wondering: The logline of your screenplay is a simple sentence or two that acts as a short synopsis of your story and provides the emotional hook that will make any agent or producer wish to read your script. You include the logline of your screenplay within your initial query letter whenever you are soliciting interest in your script from an agent or producer.

A well written logline should be carefully thought out. You have two sentences at most to convince people that your script is worth the time and effort to read, which will hopefully lead to a sale. A logline is also a useful time-saving device. If you are talking about your screenplay to anyone (from friend to Hollywood star) and they ask you what it’s about then you can simply quote your logline (but try not to sound like you memorized it). There should be something about that logline which really stands out and makes whoever hears it want to read the full story.

Your logline also allows you to “big up” your story so it sounds as high concept as possible. Producers love high concept scripts as they are easy to market. That means even if your story isn’t particularly high concept you can use you logline to embellish on it’s most intriguing points. Take note Sundance.

Again, there are two main reasons why you need a logline:

1. A logline keeps you focused as you write.

2. You need a logline to sell your screenplay.

Here are three questions to ask yourself as you write your logline:

1. Who is the main character and what does he or she want?

2. Who (villain) or what is standing in the way of the main character?

3. What makes this story unique?

The Fugitive: After he's wrongly convicted of murdering his wife, a high-powered surgeon escapes custody and hunts down the real killer, a one-armed man.

Memento: A man, suffering from short-term memory loss, uses notes and tattoos to hunt for the man he thinks killed his wife.

Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind: A couple undergo a procedure to erase each other from their memories when their relationship turns sour, but it is only through the process of loss that they discover what they had to begin with.

Contests will also ask for loglines. Even your granny is going to ask for a logline. There's no way around it.

I may have been a little harsh with my friend, but that's exactly how I am going to be judged as a writer. Do you want to be perceived as a professional or as an amateur wannabe?

Wednesday, June 09, 2010

The True Power of Positive Thinking

I just discovered a use for positive thinking. Your excuses won’t be questioned and you can get out of anything.

Friend: Do you want to run a half-marathon on October 24th?

Me: I can’t. My calendar says the Austin Film Festival is from Oct. 21-28 and I’m going to be a screenplay finalist. I have to attend. Sorry dude.

Friend: Can you help me move second week of January?

Me: Oh shoot! I’m gonna be at the Sundance Screenwriter’s Lab.

Friend: How about the week after that?

Me. Can’t. I’ll have a short film in the festival.

Friend: You’re a delusional wacko and I don’t want to be around you until you get help.

Et voila!

Tuesday, June 08, 2010

If you submitted to Nicholl...

Last year, in the first round: all scripts read once. About 2800 read twice. About 800 read three times. It will be similar this year. Of the first two reads, only one has to be highly rated to garner a third read. After three reads, best two of three are tallied and highest scoring scripts advance to the quarterfinal round.

Are you a writer?

I just came across this quote:

“I could be just a writer very easily. I am not a writer. I am a screenwriter, which is half a filmmaker… But it is not an art form, because screenplays are not works of art. They are invitations to others to collaborate on a work of art.”--Paul Schrader

Do we agree with this? He’s got a point but I’m not so sure. And if it is true, or if we convince ourselves that it is true, then is all that work in vain?

The following really pushes the point:

“Out of the thousand writers huffing and puffing through movieland there are scarcely fifty men and women of wit or talent. The rest of the fraternity is deadwood. Yet, in a curious way, there is not much difference between the product of a good writer and a bad one. They both have to toe the same mark.”--Ben Hecht

Should we just concentrate on premise and high concept and stop being so goddam precious with our words?

Can you do that? I don’t think I can.

“I could be just a writer very easily. I am not a writer. I am a screenwriter, which is half a filmmaker… But it is not an art form, because screenplays are not works of art. They are invitations to others to collaborate on a work of art.”--Paul Schrader

Do we agree with this? He’s got a point but I’m not so sure. And if it is true, or if we convince ourselves that it is true, then is all that work in vain?

The following really pushes the point:

“Out of the thousand writers huffing and puffing through movieland there are scarcely fifty men and women of wit or talent. The rest of the fraternity is deadwood. Yet, in a curious way, there is not much difference between the product of a good writer and a bad one. They both have to toe the same mark.”--Ben Hecht

Should we just concentrate on premise and high concept and stop being so goddam precious with our words?

Can you do that? I don’t think I can.

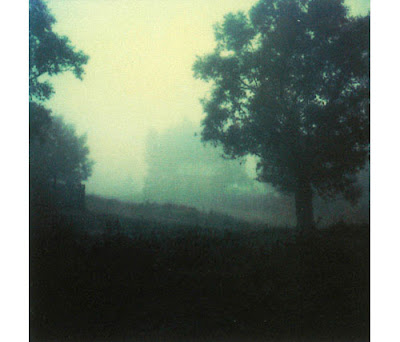

A poet with a Polaroid camera.

A few days ago I told someone I was the least spiritual person in the world. I just remembered that’s not entirely true. All it takes is the mere sight of this word to make me believe in humanity, in nature, sometimes even in myself:

Tarkovsky

I wrote that essay as part of my application to the Telluride Film Festival Student Symposium.* The question was: If you could only take one film with you to the future, which one would you choose and why? (I got in and, so far, my participation in the Symposium has been the highlight of my film career. If you have been to the Telluride Film Festival, you probably understand why.)

These photos, taken at home and in Italy, bear witness to the same way of seeing and visual world as the great films. A selection from these photos was first published in Italy in 2006, and recently a Russian photo blog digitized all the pictures. I hope you enjoy them as much as I do.

“An artist never works under ideal conditions. If they existed, his work wouldn’t exist, for the artist doesn’t live in a vacuum. Some sort of pressure must exist. The artist exists because the world is not perfect.”

“My purpose is to make films that will help people to live, even if they sometimes cause unhappiness.”

“So much, after all, remains in our thoughts and hearts as unrealized suggestion.”

“I think in fact that unless there is an organic link between the subjective impressions of the author and his objective representation of reality, he will not achieve even superficial credibility, let alone authenticity and inner truth.”

"We can express our feelings regarding the world around us either by poetic or by descriptive means. I prefer to express myself metaphorically. Let me stress: metaphorically, not symbolically. A symbol contains within itself a definite meaning, certain intellectual formula, while metaphor is an image. An image possessing the same distinguishing features as the world it represents. An image — as opposed to a symbol — is indefinite in meaning. One cannot speak of the infinite world by applying tools that are definite and finite. We can analyze the formula that constitutes a symbol, while metaphor is a being-within-itself, it's a monomial. It falls apart at any attempt of touching it. "

“My encounter with another world and another culture and the beginnings of an attachment to them had set up an irritation, barely perceptible but incurable-rather like unrequited love, like a symptom of the hopelessness of trying to grasp what is boundless, or unite what cannot be joined; a reminder of how finite, how curtailed, our experience on earth must be.”

* Interesting side note: Joe Swanberg of Mumblecore fame, was one of my condo roommates. He showed us a video he did of his brother and his friends skateboarding.

Tarkovsky

I wrote that essay as part of my application to the Telluride Film Festival Student Symposium.* The question was: If you could only take one film with you to the future, which one would you choose and why? (I got in and, so far, my participation in the Symposium has been the highlight of my film career. If you have been to the Telluride Film Festival, you probably understand why.)

These photos, taken at home and in Italy, bear witness to the same way of seeing and visual world as the great films. A selection from these photos was first published in Italy in 2006, and recently a Russian photo blog digitized all the pictures. I hope you enjoy them as much as I do.

“An artist never works under ideal conditions. If they existed, his work wouldn’t exist, for the artist doesn’t live in a vacuum. Some sort of pressure must exist. The artist exists because the world is not perfect.”

“My purpose is to make films that will help people to live, even if they sometimes cause unhappiness.”

“So much, after all, remains in our thoughts and hearts as unrealized suggestion.”

“I think in fact that unless there is an organic link between the subjective impressions of the author and his objective representation of reality, he will not achieve even superficial credibility, let alone authenticity and inner truth.”

"We can express our feelings regarding the world around us either by poetic or by descriptive means. I prefer to express myself metaphorically. Let me stress: metaphorically, not symbolically. A symbol contains within itself a definite meaning, certain intellectual formula, while metaphor is an image. An image possessing the same distinguishing features as the world it represents. An image — as opposed to a symbol — is indefinite in meaning. One cannot speak of the infinite world by applying tools that are definite and finite. We can analyze the formula that constitutes a symbol, while metaphor is a being-within-itself, it's a monomial. It falls apart at any attempt of touching it. "

“My encounter with another world and another culture and the beginnings of an attachment to them had set up an irritation, barely perceptible but incurable-rather like unrequited love, like a symptom of the hopelessness of trying to grasp what is boundless, or unite what cannot be joined; a reminder of how finite, how curtailed, our experience on earth must be.”

* Interesting side note: Joe Swanberg of Mumblecore fame, was one of my condo roommates. He showed us a video he did of his brother and his friends skateboarding.

Sunday, June 06, 2010

The Wild Bunch

Should we study and look up to greatness even if seems outdated vis a vis today's screenwriting standards? This question came up during tonight's #scriptchat discussion of the Chinatown screenplay and continued for a couple of hours later. I will elaborate in the next post. But for now, since I referenced both The Wild Bunch screenplay and Rembrandt during the chat, I thought I'd post an article I wrote about this movie for an ezine I used to write for, which expresses my intense feelings for this masterpiece.

The Wild Bunch

Dir: Sam Peckinpah

1969

After seeing The Wild Bunch for the first time, my reaction was: "If this is a movie, then what have I been watching all my life?" I got depressed. Because there was no way I could even come close to such achievement, the film made me feel that I should quit making movies. I questioned my talent, my ability and above all, my courage. Six million dollars, 81 shooting days, 330,000 feet of film, 1288 camera set ups and 3,600 shot-to-shot edits later, Sam Peckinpah changed the face of cinema and my idea of what truly great filmmaking was about.

Peckinpah had been fired from his last film, and after three years of unemployment, The Wild Bunch was his opportunity to direct again. In its simplest terms, the story is about bad men in changing times, or as Peckinpah himself put it: "what happens when killers go to Mexico." It's an unrelenting, bleak tale about aging, scroungy outlaws bound by a private code of honor, camaraderie and friendship. The lone band of men ("the Bunch"), led by Pike Bishop (William Holden), have come to the end of the line and no longer are living under the same rules in the Old West. They are being stalked relentlessly by bounty hunters, one of whom is Pike's former friend Deke Thornton (Robert Ryan), who would side with the outlaws if it weren't for the threat of being sent back to Yuma Prison. In the bloody opening sequence, the Bunch ride into Starbuck, a dusty, small town. They hold up the bank and in the process annihilate the town. However, the job is a set-up: the loot they get away with is worthless steel washers. To escape the bounty hunters they cross the border into Mexico, where they agree to do a job for the dictatorial Mexican General, Mapache (Emilio Fernandez). It is to be their last job.

In the context of the times, the much-imitated and influential film was considered extremely violent. It's impossible to determine whether it's the most violent "ever made," or if it was the most violent of its time, and the question is probably irrelevant. What can be said is that with the newly gained freedom attained through the development of the Code and Rating Administration and in the midst of a volatile zeitgeist, Peckinpah, with the help of the brilliant editor Lou Lombardo and cinematographer Lucien Ballard, developed a stylistic approach that, through the use of slow-motion, multi-camera filming and montage editing, seemed to make the violence more intense and visceral. Peckinpah's intent was to "take the facade of movie violence and open it up, get people involved when they start to go into the typical Hollywood/television reaction syndrome and then twist it so it's not fun anymore--just a wave of sickness in the gut."

Who would rob, kill, steal guns, give the guns away to the peasants and go back to rescue a comrade and die for him? Every Western tried pull off that story but it never worked. It's pure romance. Peckinpah's objective from the onset was to make that story work. The budget escalated and the producer, Phil Feldman, complained to Warner Bros. exec Ken Hyman, who gave Peckinpah carte blanche after seeing the footage that was coming in. Hyman knew something extraordinary was taking place in that Mexican village. Peckinpah and his crew were creating a full landscape in the fullest artistic sense; sequence after sequence, a whole world of themes and emotions play out without dialogue. Peckinpah's genius for improvisation produced brilliant sequences that materialized out of thin air. The Bunch's march to their death was a scant three-line description in the screenplay. Nobody, including Peckinpah, knew what he was going to do because he never formulated a shooting plan before arriving on location. Once he was on set, before you knew it, Peckinpah built and built and built until it became that scene. The climax, The Battle of Bloody Porch, is one of the most extraordinary sequences on film. Again, Peckinpah did not have a clue as to how he was going to shoot it. He had four cameras rolling for 12 days and, legend has it, Cliff Coleman, the assistant director, was so good that the stuntmen, actors and even bullets never missed a mark, making the sequence relatively easy to edit.

As is the case with all great artists, Peckinpah had an extraordinary ability to take what people really couldn't see and turn it into something extraordinary. As the Bunch reaches the Mexican border to take refuge in a village, Angel (Jaime Sanchez), the only Mexican in the group, recognizes differences from Texas at the edge of the border river, but not the Gorch brothers (Warren Oates and Ben Johnson). Their conversation points out their cultural differences and varied perspectives:

Angel: Mexico Lindo.

Lyle: I don't see nothin' so 'lindo' about it.

Tector: Just looks like more Texas far as I'm concerned.

Angel: Aw, you don't have no eyes!

That's Peckinpah speaking to the rest of the world: "you are not seeing what I'm seeing." Peckinpah was a man who wasn't afraid to look at himself as honestly as he could and to strip away the artifice that makes mainstream audiences tick. He really believed in who he was and what he could do. In a scene around the outlaws' campfire, Pike dreams of one final, successful job before retiring:

Pike: This was gonna be my last. Ain't gettin' around any better. I'd like to make one good score and back off.

Dutch: Back off to what? (No answer) Have you got anything lined up?

Pike: Pershing's got troops, spread out all along the border. Every one of those garrisons are gonna be gettin' a payroll.

Dutch (sarcastically): That kind of information is kind of hard to come by.

Pike: No one said it was going to be easy but it can be done.

Dutch: They'll be waitin' for us.

Pike: I wouldn't have it any other way.

I didn't quit. In fact, I always look to this movie to set me straight when I start to lose my way. Like Pike, I want to be able to say "I wouldn't have it any other way" and really mean it. The Wild Bunch is an uncompromising ballet in which the action, the detail, and the lives of the characters are as Peckinpah imagined they would be. After the final sequence of principal photography was completed, Bud Hulburd, the special effects engineer, remarked: "I just had the opportunity to hang a Rembrandt. It will probably never happen again." He was so right.

Friday, June 04, 2010

When Screenwriting Goes Wrong

I just received this email from the people that run the contest I just won:

"Please be informed that we have received countless emails and phone calls from one of the submitters to the Screenplay Competition. These emails and calls as well as her screenplay are incoherent and obsessive. We have tried many times to clarify to this person that the competition is over that her screenplay was not a finalist, but she continues to pursue calling and emailing. Now that names have been posted for both finalists and winners she is calling with questions about you and your screenplays. We are not answering any questions and have told her to cease contact.

"Please be informed that we have received countless emails and phone calls from one of the submitters to the Screenplay Competition. These emails and calls as well as her screenplay are incoherent and obsessive. We have tried many times to clarify to this person that the competition is over that her screenplay was not a finalist, but she continues to pursue calling and emailing. Now that names have been posted for both finalists and winners she is calling with questions about you and your screenplays. We are not answering any questions and have told her to cease contact.

We are letting you know about this since the internet makes it possible to track people down through facebook, twitter, etc. Our strong advise to you is do not respond if you get any contact from her. She lives in British Columbia, Canada, her area code is (250) and her name is Anastasia S_______. [edited out]

Just looking out for you guys. Please do let us know if you hear from her, but hopefully that will never happen."

I've heard of people reacting badly to notes and criticism, but not winning a contest? What surprises me the most is that she's Canadian. I thought Canadians didn't get angry.

Thursday, June 03, 2010

Six Ways to Come to Terms with the Sad Truth that No One Wants to Read Your Blog

Ever since I can remember, I’ve had this recurring dream. (I just had it last night as a matter of fact.) Well, more accurately, it’s a horrible nightmare. In the nightmare and any variation thereof, my family and friends make plans to go somewhere together, without me. And then they take off, leaving me sobbing and bitching. They never seem to get what I’m trying to say. Not even my mother. Especially my mother. It hurts. It really hurts.

I used to write film reviews for an ezine. At the beginning, I forwarded the link by email and posted it on Facebook. After a few months, just Facebook. In a year, I heard back from three or four people. Tops. More often, I’d get: “Did you see Such and Such a Movie?” I replied: “Yes, I reviewed it and sent the link to you.”

“Oh.”

When I wake up from the nightmare above, I realize, once again, that I have to accept that being understood is overrated. I thought I had resolved that issue after I screened my last film for my parents. For 15 minutes, they watched quietly, eyes glazed over. My mother only showed signs of life when, as my brother’s name flashed onscreen as Production Assistant (he helped me move some very heavy props.), she said, “Oh! That’s your brother.”

Still, I get a high when a stranger sees one of my films or reads one of my posts and his/her reaction lets me know they got it. I screened the same film for my best friend’s four year old. She watched enthralled. When it was over she yelled, “Again! Again!” It doesn’t happen that often. But, in reality, it’s quality over quantity that matters.

So here are my words of wisdom:

1. Your family won’t read the blog, but they will give you blood and even a kidney if you ever need one.

2. Your friends won’t either. But they’ll help you move. If you corner them and offer them plenty of booze. Hopefully you helped them move, so can use guilt to persuade them.

3. To get people to read your blog, you’re going to have to read dozens of blogs telling you exactly how to make people read your blog. Do you really want to do that?

4. If you do read all that advice, are you really going to do all that stuff? Like read other people’s blogs and comment on them? I thought so.

5. You’re a real writer. You write because you need to express yourself. It’s an addiction. It’s who you are. Keep writing. Someday, someone will be moved by what you wrote, and if you’re lucky, they’ll leave a comment.

6. So just write goddamit!

Freebie: Go to therapy if you can afford it.

Tuesday, June 01, 2010

Gus Van Sant has seen my vagina.

I never write down my dreams, let alone blog about them, but this one is film related and I find it worthy of recording for posterity.

I transitioned from one dream to another and I found myself in a desert town that looked very Terry Gilliam-ish. There were a few people around and all of a sudden I spot Gus Van Sant.

I said, “Hey Gus Van Sant, what are you doing here?”

Gus answered, “I want to make a movie with that guy.”

He pointed at an old man that just sat there and was completely uninterested in his surroundings. So Gus asked me to help him make the movie. You can imagine how excited I was. My first impulse was to Tweet about it but I didn’t have a computer. Gus and I walked around the town trying to find cast and crew members.

We came up to a goofy woman and he said, “You! You’re gonna be the AD.”

I said, “Are you sure about that Gus?”

He said, “Any movie I make outside the studio system, I do like this.”

I said “Oh, that explains Gerry.”

I looked down and I noticed I wasn’t wearing a bottom. No pants, no skirt, no underwear. We continued on our search for cast and crew and although they noticed I was al fresco, no one said anything or seemed to care. To make matters worse, I kept on bending over to pick up stuff.

Gus and I then went to the “production office” which was a wooden shack right out of a Western. He had a laptop and I noticed he was already tweeting about the new film. I felt envious. I asked him if I could send a tweet and he said, “No, we’ve got a lot of work to do.” I sat down on the desk, legs dangling and as I look up I see Gus’s horrified face. I looked down and my legs were open.

He said, “Is that what it looks like?!”

I remembered that Gus was gay, so my panic subsided.

I told Gus, “Yes, but they come in all shapes and sizes.”

He said, “Oh.”

And that’s all I remember.

Maybe someone can enlighten me and let me know what all this means.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)